Uncertainties in Pediatric Gene Therapy: Takeaways from a Lunchtime Lecture Series

Cara Hunt, Alison Bateman-House, PhD, MPH, & Lesha D. Shah, MD - March 04, 2022

Read about a lunchtime lecture series from the Pediatric Gene Therapy and Medical Ethics Working Group.

Gene therapy is still a new field, though it has begun to meet its promise, with seven gene therapies (GTs) having been approved by the FDA (including CAR-Ts). Many more candidate GTs are currently in clinical development. Genetics, as a field, has been acutely aware of the relevance of ethical, legal, and social issues (ELSI) in the development and use of new technologies –– be those for screening, diagnosis, or treatment. As such, there is widespread attention to the ethical issues surrounding the development of these candidate GTs, particularly when it comes to their testing in human volunteers. The fact that a non-trivial number of these volunteers are children, who are not legally able to consent to participate in clinical trials and whose involvement in this research hinges upon permission from surrogate decision makers (often their adult caregivers), makes it all the more necessary for us to proactively examine the unique ethical challenges that accompany pediatric gene therapy research. This is what the New York University Grossman School of Medicine-based Pediatric Gene Therapy and Medical Ethics Working Group (PGTME) set out to do in our 2nd Annual Lunchtime Lecture Series (LLS) in late 2021.

Background

Last year’s iteration of the LLS, entitled Critical Discussions: Multistakeholder Perspectives on the Ethics of Pediatric Gene Therapy Research, featured five days of public discussion by multistakeholder panels, all of which engaged in some way with the topic of uncertainty. PGTME is an academic working group composed of volunteer members from the biopharmaceutical industry, patient advocacy, medicine and clinical research, as well as academia and law, and it engages with each of these key stakeholder communities to learn from them about the ethical issues present in pediatric GT research, as well as innovations being implemented to address these. Since its inception, PGTME has noted that uncertainty looms large over most discussions in pediatric gene therapy, although what it is that is uncertain may vary. For example, there is uncertainty about the safety and durability of experimental GT products, especially those being used in humans for the first time. There is further uncertainty about how best to convey such information, not only to adult decision makers but also to potential child participants. In a third example, there is uncertainty about the ethics of various trial designs, as enrolling older participants would increase their ability to be meaningfully involved decision makers. However, enrolling younger participants may result in increased efficacy of the experimental GT. Thus, uncertainty seemed to be an important, timely, and flexible theme around which to structure the 2021 LLS. Here we briefly describe key takeaways from the five sessions, recordings of which are freely available online.

We kicked off the series with Pediatric Gene Therapy Research in the Context of Uncertain Risk Benefit, which focused on the issue of what sponsors, clinicians, patient advocates, and other stakeholders could or should be doing to help potential and current trial participants make informed decisions in the context of myriad unknowns. Panelists from industry, clinical research, and patient advocacy stressed that better communication with potential and current trial participants and their adult decision makers comes from assessing the concerns and anxieties of the specific rare disease community involved in a GT research study; while some concerns are shared, not all GT studies raise the same issues, nor are these issues necessarily always evaluated the same way. Communication and education efforts must begin by walking families through the proposed trial from a patient-friendly perspective, keeping in mind that “patient-friendly” is not code for merely using simple language; rather, being patient friendly means being transparent, direct, and thoughtful about how sponsors and researchers balance the interests of various populations. For instance, when sponsors communicate to investors, they tend to use optimistic language, emphasizing the possibilities that might be. Yet these communications do not exist in an investor silo; they are heard by patients and families who might overtly or at least subliminally take in messages about “breakthroughs” or “potential cures” that drown out more measured messages of uncertainty that they should be hearing when contemplating trial participation. In such cases, sponsors should explain to patients why their disclosures happen in a certain schedule and promptly provide them with materials that cater to their particular questions and concerns. Understanding the fears and unknowns that families and physicians are grappling with the most is of utmost importance around calculating risks and benefits of trial participation. Adam Hartman, a program director in the division of clinical research at NINDS/NIH, indicated the importance of “having a neutral third party or at least a friend to be there during some of these discussions,” as a way to help families remember and process what can be an overwhelming amount of information. When appropriate, sponsors should scale these discussions for the child living with rare diseases, in order to ensure that they are aware, to the fullest extent possible, of what to expect in a trial. Within an evolving landscape of information, we must emphasize education that meets people where they’re at, is responsive to their concerns, explains the science, and is transparent about differences in communications with investors versus patients.

Trust and Transparency

The second panel, Trust and Transparency for Trial Participants and Families, further emphasized the need for sponsors to partner with patient advocacy groups. Panelists included a health communication researcher, adolescent psychiatrist, parent and advocate, and industry representative who was a former clinician. Collaborative approaches are win-wins; they bolster informed consent and mitigate therapeutic misconception, and also assist sponsors in designing trials with clinical endpoints that are relevant and meaningful to affected communities, in addition to regulators and payers. In order to empower and center patient voices, sponsors and researchers must set aside ample time (a common obstacle for many academic clinicians) to explain trial details i.e., differences between phases, re-dosing limitations, and the logistical implications/burdens of participation - and to contextualize/interpret information from trial sponsors so that patients and families understand all of their available options outside of the trial at hand. While there will always be uncertainty in research, we can better support shared decision making by providing adequate time, iterative dialogue, and decisional support tools necessary for patients and their caregivers to learn information, to process it, and to ask follow-up questions. Further, trial sponsors must work towards eliminating barriers to clinical trial education and access. Health communications researcher Aisha Langford pointed to historical, documented disparities on who gets asked to participate in trials; eliminating these types of barriers to equity must be prioritized if GT research is to be relevant to patients across the entire spectrum of the target disease.

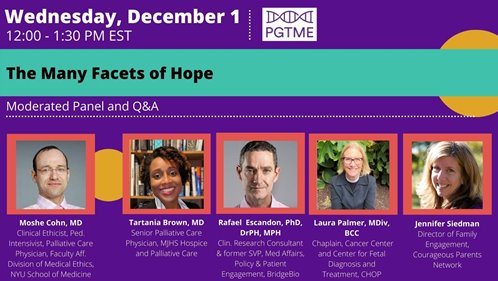

Hope

During the third panel, The Many Facets of Hope, panelists articulated how hope is a fluid concept in the GT space, one that is continually defined and redefined for patients with varying stages of disease progression and treatment options. Even as therapeutic options change or narrow, families might celebrate their hopes for other parents or for the long-term success of a project. But where families can understand such nuance, our culture does not. Tartania Brown, MD, a clinician and person living with sickle cell disease, was quick to point out how in American culture, “we use hope as a slogan…we sell hope.” Once again, speakers cautioned against labeling GT as a “cure.” As Jennifer Siedman from the Courageous Parents Network noted, “the words that we use when we talk about therapies and when we talk about research and we talk to patients and families really, really, really matter.” Dr. Brown noted that those within her disease community have lived without hope for a long time and are only recently beginning to have a seat at the table in discussions with industry and researchers. This highlights that hope, like access to GTs, is often distributed across socioeconomic lines.

.aspx?width=498&height=281)

The Lived Experience

In the fourth panel, focused on The Lived Experience of GT research, particularly the social, emotional, and practical aspects for trial volunteers and their adult decision makers, we heard from patients, advocates, and researchers about the psychological overlays of risk/benefit and the spectrum of burden of rare disease and gene therapy trial participation. Given uncertainty, panelists discussed supports that should be provided for patients to make the best decisions for themselves or their children with the caveat that these will vary between conditions and patient populations. Of interest was the inclusion of social workers or other community liaisons to spend time with families answering questions and de-emphasizing “magic bullet” connotation of GT which affects hopes and expectations. Isaac McFadyen, a patient with MPS VI, described how he experienced this in his GT trial:

"…You're always looking for signs that tell you that this has worked…whether that be a slight amount of growth, and you're like, oh, maybe it's working, or more flexible joints, or just things that you sort of imagined to be there that aren't actually there. And so then you get your hopes up. And then…you discovered that it's not really there. And well, my gene therapy did help me not have to go for ERP [enzyme replacement therapy] every week, I'm back on ERP, but I'm only doing it every second week. It’s still tough to get your hopes up and then have them sort of let down."

Panelists also discussed how burdens like travel and isolation (to avoid developing neutralizing antibodies that might disqualify a patient from a clinical trial) impact the entire family and stressed the importance of community/patient support groups and clinicians being as transparent as possible about the GT trial process. Put poignantly by Cecelia Valrie, PhD, director of the health psychology doctoral program at Virginia Commonwealth University, “We can’t stop support, and we can’t stop emotional support at any part of the process.”

Accountability and Collaboration

Closing out the week with Accountability and Collaboration with Patient Communities, panelists from industry, patient advocacy, bioethics, and academia asked what we––the stakeholder groups involved in pediatric GT research––owe not just to trial participants but to their broader disease communities and those patients who were unable to participate because of age, disease progression, lack of access (as when they are located in a different country or do not have the ability to travel to a trial site), or other exclusion criteria. Trial samples are intended as proxies for larger populations, but decisions made along the way can promote or limit the applicability of trial findings to these other patients. Pat Furlong, founder and CEO of Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, lamented that narrow inclusion criteria, “leaves all of these other people out of the equation and often out of the label…which says something about how we value [a patient’s] life after they lose ambulation.” This is why we need broad labels, Pat said, “otherwise you can’t make the case to Medicaid or it takes so long that you’re years down the road before you get an answer from them.” Another speaker put forth master protocols as a reasonable tool in this regard, one that is more inclusive with subset analysis. The way GT research is conducted within our current healthcare system begs the question of who is going to get GT versus who needs it? If we are to expand GT more equitably, we must stop “silo-ing” data; sharing data, including the specifics of adverse events, helps to establish trust within rare disease communities.

This annual series on the ethics of pediatric GT research focused, in 2021, on the ethical and policy challenges posed by uncertainty from multiple angles. Panelists shared their views, proposed policies to address these issues, and engaged in question-and-answer sessions with those in the audience. We encourage readers to listen to the captioned, recorded sessions to prompt reflection on the role that uncertainty plays in their own GT-related activities and to integrate learnings from the series.

PGTME looks forward to more discussions like these in our 3rd annual LLS this fall. In the meantime, we will continue our mission of advancing research, policy, and education regarding ethical issues surrounding pediatric gene therapy trials. To stay updated on our group’s work, please reach out to Cara Hunt (Cara.Hunt@nyulangone.org) and she will add you to the mailing list.

Ms. Hunt is the project manager for the Pediatric Gene Therapy and Medical Ethics Working Group and a research associate in the division of medical ethics at NYU Langone's department of population health.

Dr. Bateman-House is co-chair of the Pediatric Gene Therapy & Medical Ethics working group, assistant professor at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and a member of ASGCT.

Dr. Shah is co-chair of the Pediatric Gene Therapy & Medical Ethics working group, assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and a member of the ASGCT Ethics Committee.