Milwaukee High School Students Try Their Hand at Pipetting

Renee Strong - November 22, 2023

"By training teachers through the Biotech Discovery Labs program, students are getting opportunities that they otherwise may not have been exposed to in high school, or ever," writes Renee Strong, ASGCT's diversity, equity, and inclusion manager.

Read about her recent visit to Milwaukee's Rufus King High School.

Rufus King High School is a force of a building. The three-story school screams gothic architecture circa 1933 and is where around 1,500 Milwaukee teenagers receive their education.

Upon entry, I'm greeted by Mr. Moore. I inform him I'm there to see Mr. Soung in room 132 and that I'm with ASGCT. I'm carrying 15 boxes of latex-free gloves to help ease the needs of the teachers who participated in ASGCT’s Biotech Discovery Labs program last summer. It’s heavy and I see room 132. “I know him, he’s not in there yet,” Mr. Moore informs me, “but I will find him for you.” He jolts down the hall to find the missing teacher, who I soon spot exiting a classroom.

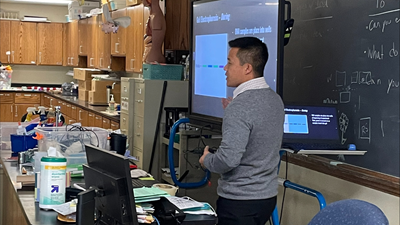

Yuepeng Soung, a biology teacher at Rufus King High School, prepares his freshmen for an electrophoresis lab.

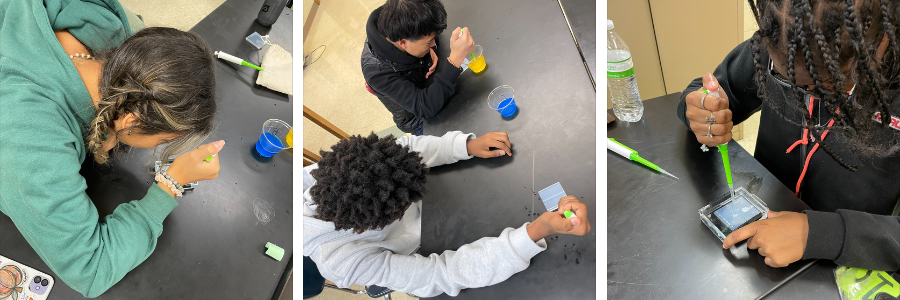

Yuepeng Soung is pushing his science cart, with a large construction paper nametag on the front. After extending his hand, he apologizes and says he teaches from a cart because there aren’t enough science labs for his classes. He is not unique in this. Most schools have teachers working without a “homebase” or classroom. “Art on a cart” is a well-known phrase in schools for teachers who “travel” within the building to provide their lessons. His cart has 12 cups of colored water: red, yellow, and blue. Through emails back and forth, I have been prepped that students are going to be practicing micro pipetting into silicone practice gels to prep for their electrophoresis lab that will come the following day. I know what this means for this freshman biology class; they are being exposed to a skill that many students don’t learn until much later in their education.

I enter a lab with old, cherry wood built-in cabinets. The details of a 1933 building are evident as well as the more modern modifications that have been added. There are two small sinks in the classroom and the 10 low lab tables are soon filled with 37 students. All the students are from underrepresented populations. All of them come in with an energy that can only be found in a classroom of freshmen.

I take a seat and Mr. Soung introduces me to the students. They smile, wave, and one girl in the front row makes a heart with her hands. I forget what it’s like to have 37 pairs of eyes on you. It’s inspiring and intimidating. Mr. Soung begins his class with a Power Point review of the day before, discussing the ins and outs of how to use a pipette. After the brief instruction, he tells the kids to come get their supplies. They all get up at once. It’s a rush, but a determined one.

“It’s not all water,” Mr. Soung says, gesturing to the colored cups. “I needed to add glycerin, which I don’t have, so I tried corn starch. I think I got the consistency right,” he adds.

If you want to find a population of people who can MacGyver a problem and be flexible in any circumstance, teachers are it. Mr. Soung’s confidence tells me this isn’t the first time that a lack of supplies forced him to pivot.

Once the students are settled, I begin to engage with them. I start with simple questions: What’s your name? Do you like science? Do you like these activities? Why? I then begin to ask about what they think about their futures.

.aspx?width=199&height=250) One student shares that she plans to be a surgeon. Her nails are painted a bright purple and her fingers gracefully work to pipette the red water into the silicone gel. I ask her if she's making plans to get there. “I know it’s going to be hard, but I am working on it,” she says.

One student shares that she plans to be a surgeon. Her nails are painted a bright purple and her fingers gracefully work to pipette the red water into the silicone gel. I ask her if she's making plans to get there. “I know it’s going to be hard, but I am working on it,” she says.

The student next to her says they like science a lot. I ask them if they plan to have a career in science.

“I am not sure, but I like it. I don’t like all the math with it, though.” Their hair covers most of their face but this doesn't affect their ability to pipette. I inform them that there are people who work with pipettes in their jobs everyday.

“Really?”

Every student seems surprised that the skills they're learning are used by people working in laboratory settings.

As I walk around, these 14- and 15-year-olds share with me what they want to do with their lives. One girl wants to be an artist. Another student says he would like to do something in business.

“I have a 3.8, but I don’t know if I can keep it up. I want to go to ASU or University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee. I want to get away from my family, but I also know I need them.”

At the same table, one student tells me he plans to be a professional athlete or a comedian. I ask for a joke, but he's focusing on his pipetting—a clear sign that this activity is more important than selling his comedic ability. This student is successfully using a broken pipette.

I believe that kids can be anything they want to be. Still, I wonder if these students have ever seen individuals who look like them in the biotechnology, science, or medical fields. Seeing themselves in these fields might strengthen their belief that they have a place there.

As I circle, students are working together on their gels. They must share. There are not enough pipettes to go around. Some students don’t have silicone gels to practice with and scroll on their phones as they wait. This is no fault of the teachers, the school, or even MPS. Funding for school districts across the country has drastically dropped over the last several decades. Teachers are working harder with less. Rufus King High School is no exception.

_3.aspx?width=250&height=250) As I am leaving, I ask Mr. Soung if he needs anything else from ASGCT.

As I am leaving, I ask Mr. Soung if he needs anything else from ASGCT.

“We don’t have enough pipettes; can I get more?” I promise to see what I can do.

ASGCT sees value in all students and supports exposure to practical science skills earlier in their high school careers. By training teachers through the Biotech Discovery Labs program, students are getting opportunities that they otherwise may not have been exposed to in high school, or ever. Lack of school funding and teacher training in these important skills is also a barrier.

ASGCT is grateful for funding from Bristol Meyers Squibb through June 2025, which provides this practical exposure. It is evident in my visit to just one of the 12 high schools we have worked with that it’s just a drop in the proverbial pipette.

Ms. Strong is ASGCT's diversity, equity, and inclusion program manager.

Related Articles