Getting to Know Ralph Yaniz, LGMD2L Patient and Advocate

Kenji Rowel Lim - June 11, 2021

We talked to Ralph Yaniz about his experience with limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2L (LGMD2L), his advocacy activities, and more.

Ralph Yaniz is a limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2L (LGMD2L) patient. He’s also a very active advocate for LGMD patients as the founder of the LGMD2L Foundation.

How did you find out that you have muscular dystrophy?

.aspx?width=125&height=235) So for me I have limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2L, which affects the anoctamin 5 protein. It's a later-in-life muscular dystrophy and also probably one of the mildest. I think among the limb girdle muscular dystrophies, it’s one of the more common ones. When I was 47, I started having some issues with my left leg. I was a big physical fitness nut, and it's crazy to think now that when I was 33 I was in the best shape of my life. I was bench pressing 300 pounds and squatting 400 pounds in my thirties. So at age 47, I noticed while jumping rope and running that my left leg was just not keeping up. The other one, it was a little stronger. And then the arms too, and there it's the opposite. My right arm unfortunately is the weak one, and my left is the strong. I just started noticing some differences. I went to the doctor and I thought maybe it was a pinched nerve. And in fact, the first doctor I saw, he looked at me and said, “get outta here, you're fine.” I'm like, “no, no, I think you need to assess me.” And when he started assessing me, he said, “oh yeah, something is not right.” So that's really how it started.

So for me I have limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2L, which affects the anoctamin 5 protein. It's a later-in-life muscular dystrophy and also probably one of the mildest. I think among the limb girdle muscular dystrophies, it’s one of the more common ones. When I was 47, I started having some issues with my left leg. I was a big physical fitness nut, and it's crazy to think now that when I was 33 I was in the best shape of my life. I was bench pressing 300 pounds and squatting 400 pounds in my thirties. So at age 47, I noticed while jumping rope and running that my left leg was just not keeping up. The other one, it was a little stronger. And then the arms too, and there it's the opposite. My right arm unfortunately is the weak one, and my left is the strong. I just started noticing some differences. I went to the doctor and I thought maybe it was a pinched nerve. And in fact, the first doctor I saw, he looked at me and said, “get outta here, you're fine.” I'm like, “no, no, I think you need to assess me.” And when he started assessing me, he said, “oh yeah, something is not right.” So that's really how it started.

Could you share with us how having LGMD2L has affected your daily life?

Remember, it's a very slow-progressing condition. At first when I found out I had it, it still had very little effect. I started learning how to go upstairs better. If they were steep, I would use my right leg instead of my left. Sometimes my knee would buckle and I would fall and I could jump right up. But it's been 15 years. Slowly, it's affected me to a great extent. I mean, I walk, but I now use a hiking pole. I use it like a cane getting out of chairs, like if I have to turn to lift myself up, unless if it's a high chair. Stairs are very hard. I also have to be careful on slippery ground because if I trip and start falling, I'm not going to be able to hold myself up.

I used to write a column for BioNews services and I wrote a lot about living creatively. At this point, I do have a brace on my left leg, which helps tremendously. Even though my right leg is a little stronger, I want to get one there too because with two braces I'll really be able to power. I even bought a wheelchair that I've only used four or five times in the year I've had it, but if I go to a museum or a baseball game, it's easier. Sometimes they give you a little folding chair and I can't get out of those anymore. I've taken some very hard falls. I've hit my head off cement walls, taking a lot of bruises and broken bones and things, but I'm adapting.

What treatment options were available to LGMD2L patients when you were diagnosed? What does the treatment landscape look like now?

It's nothing then and really nothing now. The only study with an intervention right now is the one at Northwestern Medicine here in Chicago. And that's a prednisone study (which I’m part of). (See picture at right).The Duchenne patients, they really started this. Ultimately they do weekly dosing instead of daily dosing, which prevents the side effects. So I take it just once a week, every Monday night, and I'll tell you: Tuesdays are my best day. You know, I wake up moving so well, I wish I could take it every day, but I know it's gonna hurt me. I think it's a viable treatment to slow this down. I’ve been a year and a half now on the prednisone and I feel like I've plateaued a little bit. The doctors that are doing it, I keep telling them to write the paper because they need to get this out there. I don't know of any other treatments.

It's nothing then and really nothing now. The only study with an intervention right now is the one at Northwestern Medicine here in Chicago. And that's a prednisone study (which I’m part of). (See picture at right).The Duchenne patients, they really started this. Ultimately they do weekly dosing instead of daily dosing, which prevents the side effects. So I take it just once a week, every Monday night, and I'll tell you: Tuesdays are my best day. You know, I wake up moving so well, I wish I could take it every day, but I know it's gonna hurt me. I think it's a viable treatment to slow this down. I’ve been a year and a half now on the prednisone and I feel like I've plateaued a little bit. The doctors that are doing it, I keep telling them to write the paper because they need to get this out there. I don't know of any other treatments.

Have you learned of any gene therapy research that’s being done for LGMD2L?

Other than the gene therapy research that's going on by Sarepta and other companies like that, there's only a few doing gene therapy work. I think what Sarepta has basically done is to take an AAV, take out its genetic material and replace it with a functional gene, and then give you an infusion. They've already done it for LGMD2E on humans. They're following, I think it was three children (with LGDM2E), and they've definitely been helped by that. For 2L they’re still in preclinical trials, but they're thinking within two or three years, they might reach humans. Now unfortunately I may either be too old or maybe not as strong then. That's why I'm trying to stay strong now, because I would love to be in the trial if they do get there.

What was the inspiration and thought process behind starting the LGDM2L Foundation?

Well, the impetus was interesting. My doctor is Matthew Wicklund; he's really one of the top people in this country. When I started having muscle weakness, 2L wasn't even discovered yet in 2006. They discovered it in 2010, so by 2011 I got the diagnosis and my doctor suggested I find another doctor because he didn’t know anything about it. I found Dr. Wicklund at Penn State, now he's at Colorado. And he said to me, "this is a new illness, maybe you want to be the person to start the foundation one day." And I said "oh, maybe," you know? It was in the back of my mind and when I retired, I decided to start the foundation.

Well, the impetus was interesting. My doctor is Matthew Wicklund; he's really one of the top people in this country. When I started having muscle weakness, 2L wasn't even discovered yet in 2006. They discovered it in 2010, so by 2011 I got the diagnosis and my doctor suggested I find another doctor because he didn’t know anything about it. I found Dr. Wicklund at Penn State, now he's at Colorado. And he said to me, "this is a new illness, maybe you want to be the person to start the foundation one day." And I said "oh, maybe," you know? It was in the back of my mind and when I retired, I decided to start the foundation.

What kinds of activities does the LGDM2L Foundation do?

When we first started this, I spoke to some people who said they made mistakes trying to fund research. We really didn't have the ability to do that. And so I think the most important thing you can do is to start the (patient) registry, have that built and ready to go. We still have very little information right now. It's more contact information, confirmation of diagnosis, but I need to do some natural history studies. I've set up leaders of the LGDM2L Foundation in many countries—in Germany, Denmark, England, Spain, Belgium, and France. We're going to get together and talk about trying to build a database where we can include the type of mutation, what symptoms the person has, are they in pain or not, and so on. We want to try to build this database. That'll help us understand maybe some of the differences between mutations and hopefully that'll be helpful for researchers. I want to build something that is going to help us in three years when we start human trials.

And so the registry is the main purpose for being, but obviously it's also education, information, support, and sharing. We have a Facebook site with almost 200 people where they put up questions, share information on knee braces, on sleep aids, on pain, on what you do, etc. I've also been coordinating international calls for small groups, six or seven people on Zoom, where we talk about our symptoms and bounce ideas off each other. I'm really sorry the COVID issues happened because last year, I was going to do five or six meetings around the country. This year, I was maybe going to go to Europe and do a couple of face-to-face meetings, and really build that community. We haven't been able to do any of that, but maybe by the end of this year or next, I can do those and really get us meeting face-to-face.

And so the registry is the main purpose for being, but obviously it's also education, information, support, and sharing. We have a Facebook site with almost 200 people where they put up questions, share information on knee braces, on sleep aids, on pain, on what you do, etc. I've also been coordinating international calls for small groups, six or seven people on Zoom, where we talk about our symptoms and bounce ideas off each other. I'm really sorry the COVID issues happened because last year, I was going to do five or six meetings around the country. This year, I was maybe going to go to Europe and do a couple of face-to-face meetings, and really build that community. We haven't been able to do any of that, but maybe by the end of this year or next, I can do those and really get us meeting face-to-face.

Now in 2019, several groups did help organize the first limb girdle muscular dystrophy meeting in Chicago. We had over 400 people attend and this year in September will be the second one. We're going to do it every other year. This year, because of what's happened, we're going to do it all virtual. We're expecting to probably have a thousand people or more, and a lot of the companies attend too.

Can you tell us about some of the other advocacy work you do?

What we did last year is our first ever lobby day on Capitol Hill. Again with COVID, it ended up having to be virtual. In my career, I did a lot of lobbying of legislators. I worked for AARP for about 13 years, and our work there was lobbying, passing laws, and connecting with legislators. Many of us got together and did an online lobbying event, where we had people writing emails and letters to their elected officials looking at issues around accessibility: both physical, like being able to access a building or a restaurant, and then also just the accessibility of healthcare. And ultimately, when we get there, accessibility to genetic treatments. We know when those come along, they're going to be expensive and how will people access what's available if we do find some treatments and cures? The event went well. It may end up being virtual again, but I hope maybe by next year we can all be live, in wheelchairs or whatever, at Capitol Hill in Washington DC.

For 2L they’re still in preclinical trials, but they're thinking within two or three years, they might reach humans. . .That's why I'm trying to stay strong now, because I would love to be in the trial if they do get there.

Ralph Yaniz

Based on your experience, why is advocacy important?

I think there are about 7,000 rare diseases, and a good percentage of those are genetic disorders. They're all very rare. Most people don't understand; they don't really know what it's like to live with that. I think the advocacy is for really getting people to understand. Sometimes it's very simple, like setting up accessibility in places such as restaurants, having different types of seating, ensuring the ability of wheelchairs to enter. But still, sometimes you go to places and you don't really have a way to get through even 30 years after the Americans with Disabilities Act in this country. We really aren't there yet. So I think advocacy is important because I think it really leads us to a better place in terms of living with the illness. I also think it leads us to the possibility of one day finding those treatments and cures and getting the money and the funding for NIH and everything else. We're really on the cusp, between CRISPR technologies and genetic therapies and medications and drugs, I think we may really see some big things happening in this field in the next 10 years.

What was your most unforgettable experience as a patient advocate?

For me, I think probably the biggest one was the lobby day we did last year. Everybody, we all did a little (lobbying) training and then everybody wrote letters. And then they let me know afterwards which senators they spoke with and how it went. We also sent them information and materials. And so just the fact that these 40 or 50 people came out and really felt they made a difference for the day was for me the biggest thing in terms of the advocacy work we've done.

Do you have any message for researchers working on finding therapies for genetic diseases?

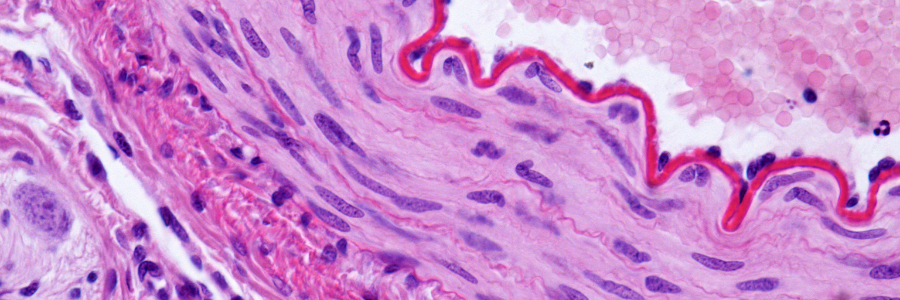

I think the message is that it's very important to figure out exactly what goes on despite how complicated it is. At least from my perspective, it seems like we might be able to reach treatments and cures before really fully understanding what is happening at a cellular level. It's almost like COVID, I mean, I don't think they've really figured out all the things that it can do to you, but they can make a vaccine. Well, it's the same with genetic therapy. They might be able to replace the gene, they might be able to fix it, but they may not fully understand it.

My doctor always reminds me, we're all different. We could have the same mutation, but we also have 20,000 other genes that are playing a part in our life. And so the way this mutation affects me could be very different. You may have a variant of unknown significance (in some other gene) that maybe does have significance and causes more problems with that mutation or with another gene. Sometimes, I hear symptoms people have that are very unique to their situation because of their own genetic makeup. So I think my message to researchers is that even if we get to the point where we can fix some of this, let's really try to understand all the ramifications of the genetics. I know we've kind of almost mapped that entire genome, but I don't think we fully understand it. It's so complicated. But you know, I would tell researchers too that we're fighting for you because we're looking for more money, more equipment—whatever you need, we need more of it. In our country, we have the money, we have the power to do that. We've proven that and we have to make it a priority.

My doctor always reminds me, we're all different. We could have the same mutation, but we also have 20,000 other genes that are playing a part in our life.

Ralph Yaniz

How can researchers get involved with patient advocacy?

I think it's knowing where the patient community is and just making sure that as they get new information they can share it to us, or if they need some information they can reach out. For example, Dr. Criss Hartzell at Emory was working with a couple of researchers at Harvard who were looking at 2L. The Harvard researchers connected them with me, and ultimately his group was able to take a skin biopsy from me for research. I haven't heard yet the outcomes, but this is one of the things that researchers should reach out to us with, because we might be able to connect them to patients who are willing to help. I've given five muscle biopsies and I'm willing to give five more if there are researchers that want some of my muscles or some of my cells.

Do you have any message for other patients who are living with a genetic disease?

.aspx?width=300&height=219) I think it's maintaining a positiveness as much as they can and being creative. It’s really knowing that sometimes when we give up too easily, we don't get to find some of the solutions, whether it's a knee brace or a special chair or something that allows you to move better or things of that nature. I just tell people, we're getting very close, both on the assistive technology and on our understanding of the genetic science. And so really stay strong, stay as strong as you can so you can get there.

I think it's maintaining a positiveness as much as they can and being creative. It’s really knowing that sometimes when we give up too easily, we don't get to find some of the solutions, whether it's a knee brace or a special chair or something that allows you to move better or things of that nature. I just tell people, we're getting very close, both on the assistive technology and on our understanding of the genetic science. And so really stay strong, stay as strong as you can so you can get there.

Kenji Rowel Lim is a Ph.D. candidate in medical genetics at the University of Alberta, Canada, and a member of the ASGCT Communications Committee.