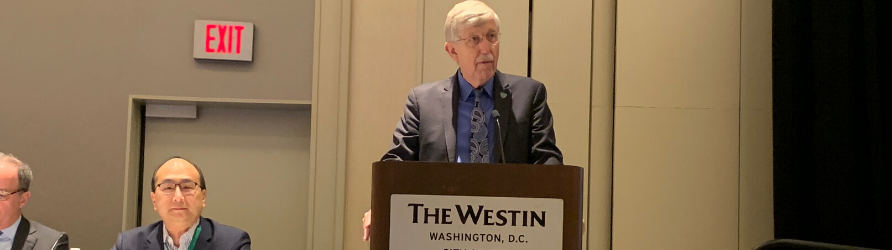

NIH’s Collins Calls for Germline Gene Editing Moratorium at Policy Summit

ASGCT Staff - November 06, 2019

NIH Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D. called for a worldwide moratorium on clinical uses of human germline gene editing, while defending ongoing and future applications of therapeutic somatic gene editing, on the third day of the ASGCT Policy Summit on November 6.

“Who speaks for society?” Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), asked during his keynote address at the third and final day of the ASGCT Policy Summit. Collins’ talk demonstrated his support for an international moratorium on clinical germline gene editing—the editing of eggs, sperm, or fertilized embryos that result in birth.

“I do believe this is an appropriate moment to have a moratorium on any future attempts at human clinical germline gene editing,” Collins said.

Collins did, however, draw a stark line between ongoing work in somatic gene editing to treat an individual and germline gene editing, the latter of which could be passed down through future generations and includes largely unanswered questions surrounding safety and efficacy. The ethical implications of clinical germline gene editing, Collins said, are profound, and that “we should proceed in that direction not at all at the moment, and only with great caution in the future.”

Why a Moratorium?

The call for a moratorium stems from the November 2018 announcement during the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing that a Chinese scientist used CRISPR to genetically modify embryos that were subsequently implanted and resulted in the birth of twins, an event Collins called “remarkably naive and indefensible.”

According to Collins, approximately 30 countries have existing legislation or regulation that directly or indirectly prohibit clinical uses of heritable germline gene editing like those reported by He Jiankui.

“Part of the issue is the unknown safety impacts,” Collins said as he expressed a desire for continuing independent oversight on the condition of the twins. External access to the twins would allow for continuing monitoring for off-target effects and independent analysis of the consequences. Politics between the United States and China would likely complicate any formal effort from the NIH to study the twins, Collins suggested it may be more appropriate for others to pursue that scientist-to-scientist.

“What does it mean to do a fully informed societal consultation about a technology that addresses the fundamental question of what it means to be human?” Collins asked those in attendance at the ASGCT Policy Summit. “The reason this moratorium is important, and should not be lifted until a country can address this, is to get that conversation started.”

Continuing Safe, Effective Research

Collins was careful to separate clinical germline gene editing from somatic gene editing, the latter of which, he says, NIH supports through safe and effective development of in vivo human studies, new delivery systems, new editing tools, assessment of unintended biological effects, and as a dissemination and coordinating center.

Just last week Collins and the NIH announced a four-year, $200 million partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to develop affordable, gene-based treatments for HIV and sickle cell disease.

“It would be unethical for NIH and the Gates Foundation to continue down this path without realizing that most children with sickle cell disease in Africa don’t make it to their fifth birthday,” Collins said of the challenges surrounding not only quickly identifying and treating children in Africa with sickle cell disease, but of providing equitable access worldwide. Dramatic technological advances in last decade offer an incredible opportunity, Collins said, but most treatments are complex, costly, and not yet available for most diseases.

“I’m glad to see other groups become a part of this, including ASGCT,” Collins said of the growing momentum behind a moratorium. A group of more than 60 individual scientists, bioethicists, and biotechnology executives, including past-presidents and current board of directors members from ASGCT, across industry and academia called for collaboration on a binding global moratorium on human clinical germline experimentation in a letter to U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar on April 24.

In a separate correspondence that also appeared in Nature in March, Collins and Carrie D. Wolinetz, Ph.D., associate director for science policy at NIH, wrote that they support the moratorium because the practice has the potential to “rewrite the script of human life.”

The U.S. currently prohibits federal funding to be used for any research that includes editing of human embryos. Additionally, the FDA is prohibited from considering clinical trial applications in which a human embryo is intentionally created or edited to include a heritable genetic modification.

Related Articles